“The world has been fed many lies about me..”

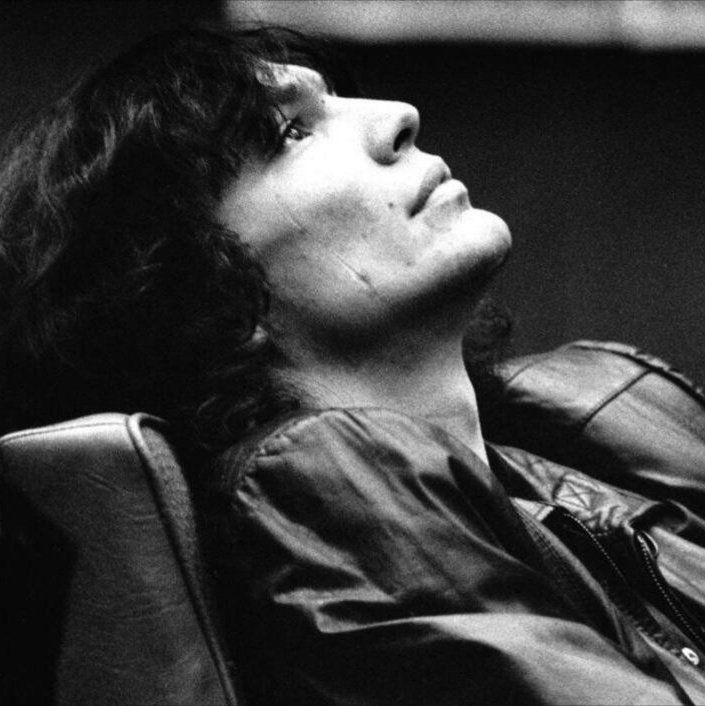

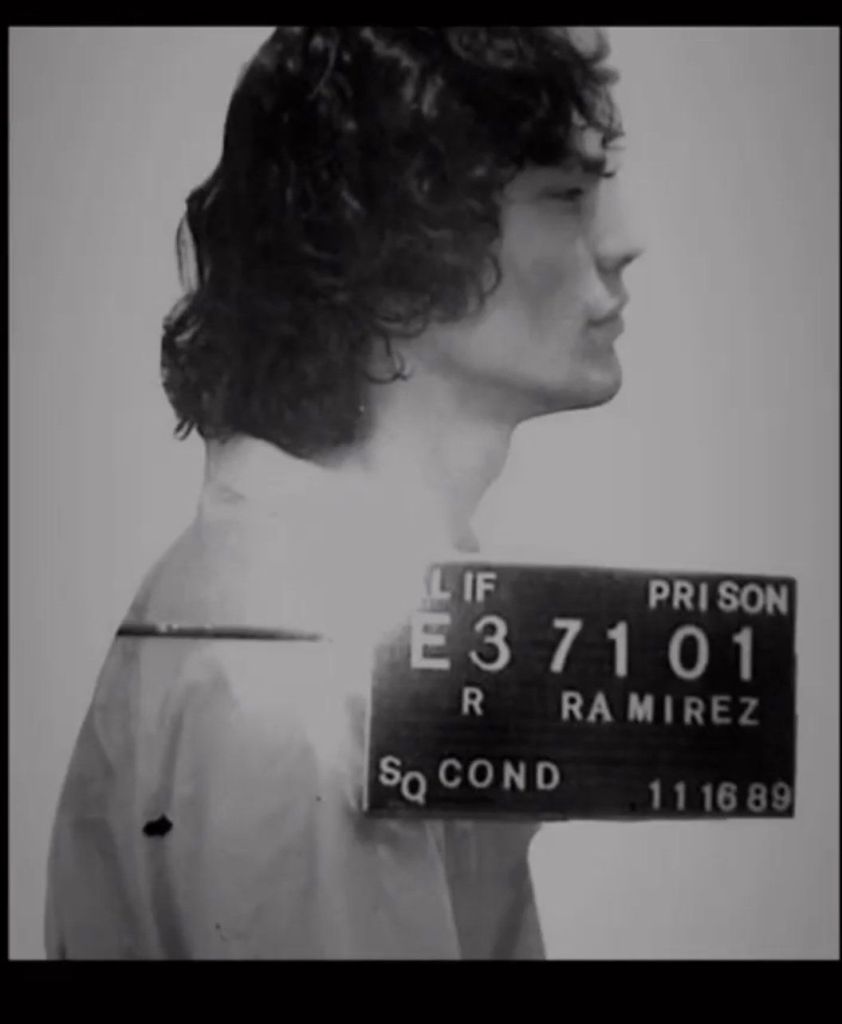

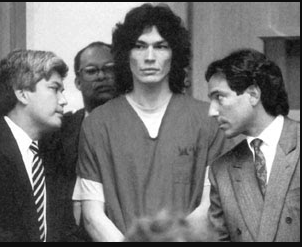

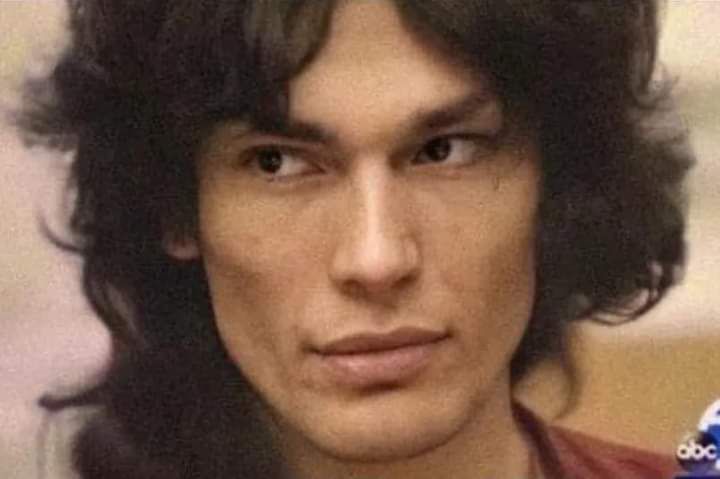

Richard Ramírez

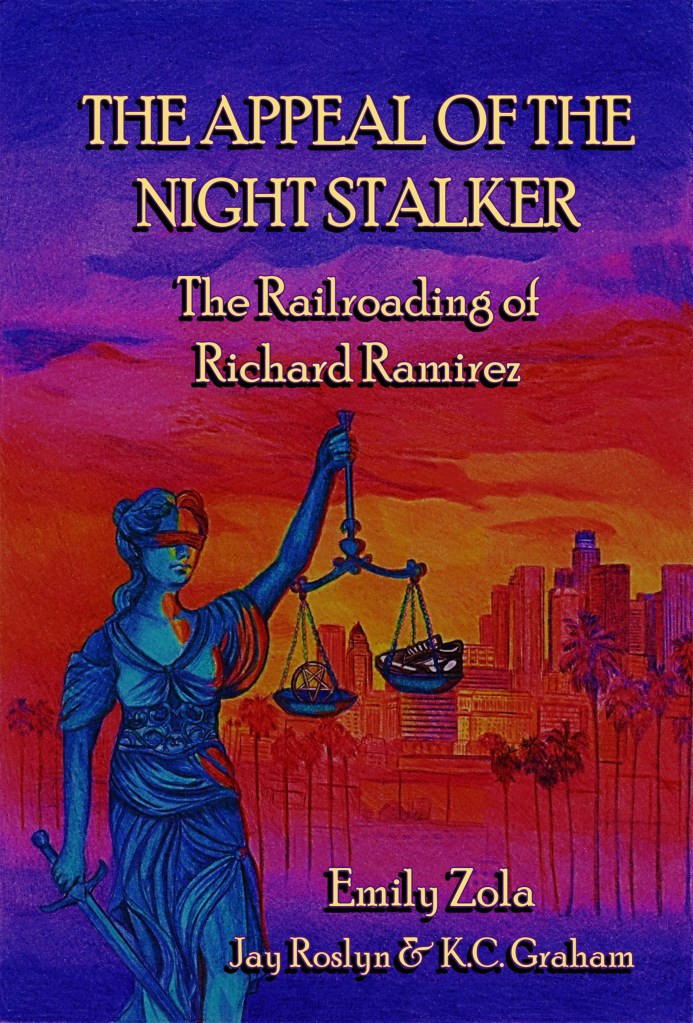

Now available, the book: The Appeal of the Night Stalker: The Railroading of Richard Ramirez.

Welcome to our blog.

This analysis examines the life and trial of Richard Ramirez, also known as The Night Stalker. Our research draws upon a wide range of materials, including evidentiary documentation, eyewitness accounts, crime reports, federal court petitions, expert testimony, medical records, psychiatric evaluations, and other relevant sources as deemed appropriate.

For the first time, this case has been thoroughly deconstructed and re-examined. With authorised access to the Los Angeles case files, our team incorporated these findings to present a comprehensive overview of the case.

The Writ of Habeas Corpus

The literal meaning of habeas corpus is “you should have the body”—that is, the judge or court should (and must) have any person who is being detained brought forward so that the legality of that person’s detention can be assessed. In United States law, habeas corpus ad subjiciendum (the full name of what habeas corpus typically refers to) is also called “the Great Writ,” and it is not about a person’s guilt or innocence, but about whether custody of that person is lawful under the U.S. Constitution. Common grounds for relief under habeas corpus—”relief” in this case being a release from custody—include a conviction based on illegally obtained or falsified evidence; a denial of effective assistance of counsel; or a conviction by a jury that was improperly selected and impanelled.

All of those things can be seen within this writ.

The Writ of Habeas Corpus is not a given right, unlike review on direct appeal, it is not automatic.

What happened was a violation of constitutional rights, under the 5th, 6th, 8th and 14th Amendments.

Demonised, sexualised and monetised.

After all, we are all expendable for a cause.

- ATROCIOUS ATTORNEYS (4)

- “THIS TRIAL IS A JOKE!” (8)

- CONSTITUTIONAL VIOLATIONS (9)

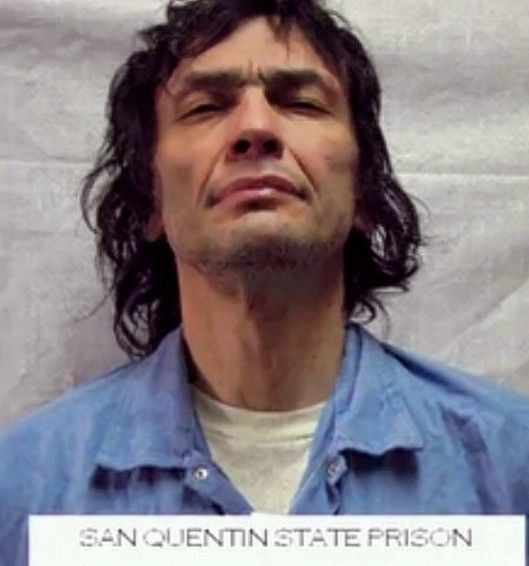

- DEATH ROW (3)

- DEFENCE DISASTER (7)

- INFORMANTS (6)

- IT'S RELEVANT (16)

- LOOSE ENDS (15)

- ORANGE COUNTY (3)

- POOR EVIDENCE (16)

- RICHARD'S BACKGROUND (6)

- SNARK (12)

- THE BOOK (4)

- THE LOS ANGELES CRIMES (22)

- THE PSYCH REPORTS (14)

- THE SAN FRANCISCO CRIMES (5)

- Uncategorized (5)

-

You, the Jury

Questioning

The word “occult” comes from the Latin “occultus”. Ironically, the trial of an infamous occultist and Satanist is the epitome of the meaning of the word itself: clandestine, secret; hidden.

We’ve written many words; a story needed to be told, and we created this place to enable us to do just that.

Here, in this space, we intended to present the defence omitted at Richard Ramirez’s trial in violation of his constitutional rights. Our investigations have taken us down roads we’d rather not travel along, but as we did so, we realised that there was so much hidden we could search for a lifetime and still not see the end of it. Once we’d started, there was no turning back; we followed wherever it led.This was never about proving innocence; that was never the intent or purpose. We wanted to begin a dialogue, allowing this information to be freely discussed and for us to verbalise the rarely asked questions. We asked, and we’re still asking.

We can’t tell you, the reader, what to think; you must come to your own conclusions, as we did.

And so

We’ve said what we came here to say; with 114 articles and supporting documents, we’ve said as much as we can at this point.

This blog will stand as a record of that, and although we will still be here, we intend to only update if we find new information, if we suddenly remember something we haven’t previously covered, or to “tidy up” existing articles and examine any new claims (or expose outrageous lies) that come to light. The site will be maintained, and we’ll be around to answer any comments or questions.

What Next?

We will focus on the book being worked on; we’ve also been invited to participate in a podcast. When we have dates for those, we’ll update you.

The defence rests? Somehow, I sincerely doubt that; ultimately, we’re all “expendable for a cause”.

~ J, V and K ~

-

The Devoted Son

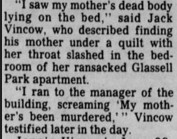

After months of persistent efforts to obtain documents from the LA Archives and Record Center regarding Richard’s case, we finally received hundreds of pages of transcripts from the preliminary hearing. However, it was a small fraction of what we are seeking, as we received a limited number of documents from 1985 and 1986. Nonetheless, within those transcripts, we uncovered interesting information that sheds light on the relationship between Jack Vincow and his mother, Jennie.

The day Jennie Vincow was brutally murdered, she was found lying in bed, with her feet toward the headboard, dressed in what appeared to be a nightgown. A blanket was lying on top of her, partially tucked around her, covering her body up to the lower portion of her neck. The medical examiner, Lawrence Cogan, reported that she had suffered multiple stab wounds to her body and a deep slash wound to her neck. Several of the wounds she suffered had the potential to be fatal on their own. Cogan also emphasized the significance of the stab wounds being located on the front of her body, indicating that the assailant and victim were likely in a face-to-face position when the wounds were inflicted.

(Statement by Detective Jessie Castillo, Court Reporter Transcripts, 3-4-86)

By all available accounts, including the 2008 Federal Habeas Corpus Petition and various contemporary news reports, Jack Vincow was portrayed as a devoted and loving son who was deeply attentive to his mother, Jennie. However, the court transcripts from March 4 and March 5, 1986, reveal some interesting findings that contradict the widely accepted portrayal of Jack as a caring son.

Appearance of Jennie Vincow’s living room the day she was found murdered

Monrovia News Post, March 5, 1986

Jack Vincow was reportedly a caring and attentive son who visited his mother daily. Yet, the condition of Jennie’s apartment on the tragic day of her death raises questions about the image of Jack as a caring son and contrasts sharply with the portrayal of filial devotion. When LAPD officers arrived at the scene on June 28, 1984, they found the apartment in a disarray. It was assumed that whoever had murdered Jennie had ransacked the home in search of valuables. However, the condition of the apartment indicated much more than mere ransacking. In Jennie’s bedroom was a chest of drawers; four drawers were pulled out, with clothing both hanging out of the drawers and strewn across the floor. The contents of a brown vinyl purse were spilled on the floor, and various items were randomly placed on top of the dresser, including two pairs of shoes and toiletries. Papers were also scattered across the floor. The kitchen table was cluttered with an assortment of items, including two Soup bowls (discussed in a previous post), several boxes of cereal, Styrofoam cups, soup cans, and a plastic dish. Upon inspecting the refrigerator, officers found it “very dirty and filthy,” with several open cans of soup and rotting food, causing a foul stench. The condition of the refrigerator led Detective Jessie Castillo to express disbelief that anyone could continue to use it in such a state. Several LAPD officers described the home as overall “unkempt, very dirty, and filthy,” indicating it was in a deplorable state and appeared to have been in that condition for a long time.

from Los Angeles Times January 31, 1989

Jack claimed he was “very close to his mother.” Would a devoted son allow his elderly mother to live among filth and rotting food? The harsh reality of Jennie’s living situation stands in stark contrast to the image of Jack as a caring son who was involved in his mother’s care, undermining his credibility.

Overkill

Was Jennie’s murder an example of “overkill”? Overkill refers to the excessive trauma inflicted on a victim that goes beyond what is necessary to cause death. Some homicide investigators argue that the presence of overkill indicates a crime of passion and suggests a connection between the perpetrator and the victim. Additionally, the act of covering a body may indicate that the perpetrator had a relationship with the victim and was remorseful. Jennie suffered multiple wounds, several of which could have been fatal on their own. She was discovered in bed, covered and “tucked in” with a blanket, suggesting the presence of overkill in the brutality of her murder.

KayCee

-

Another Lying Victim

By Venning

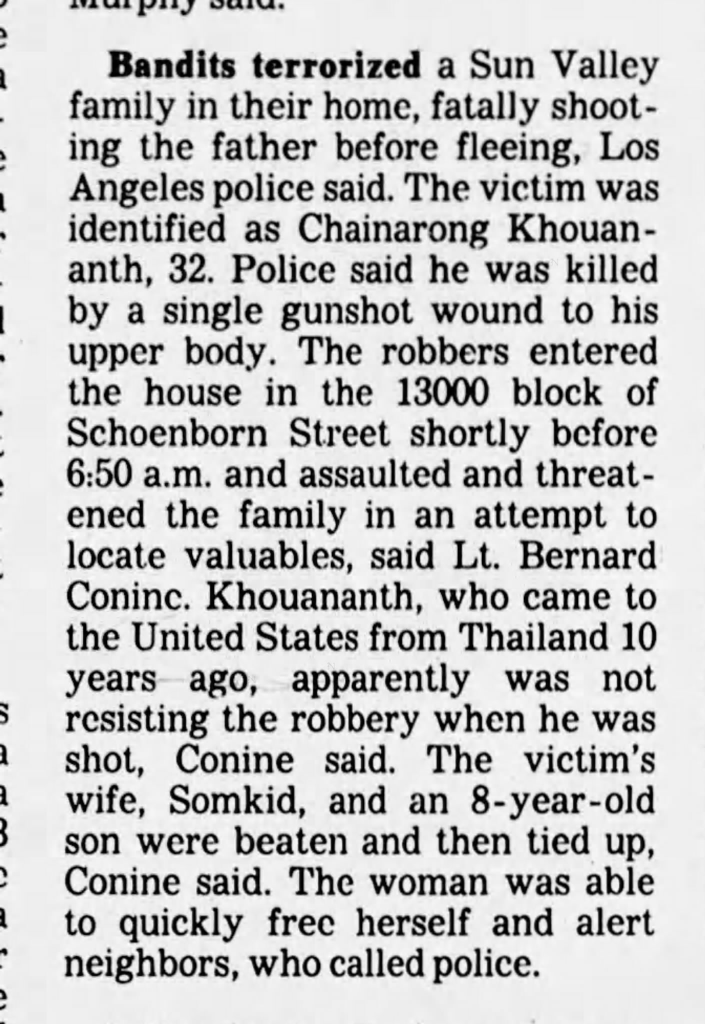

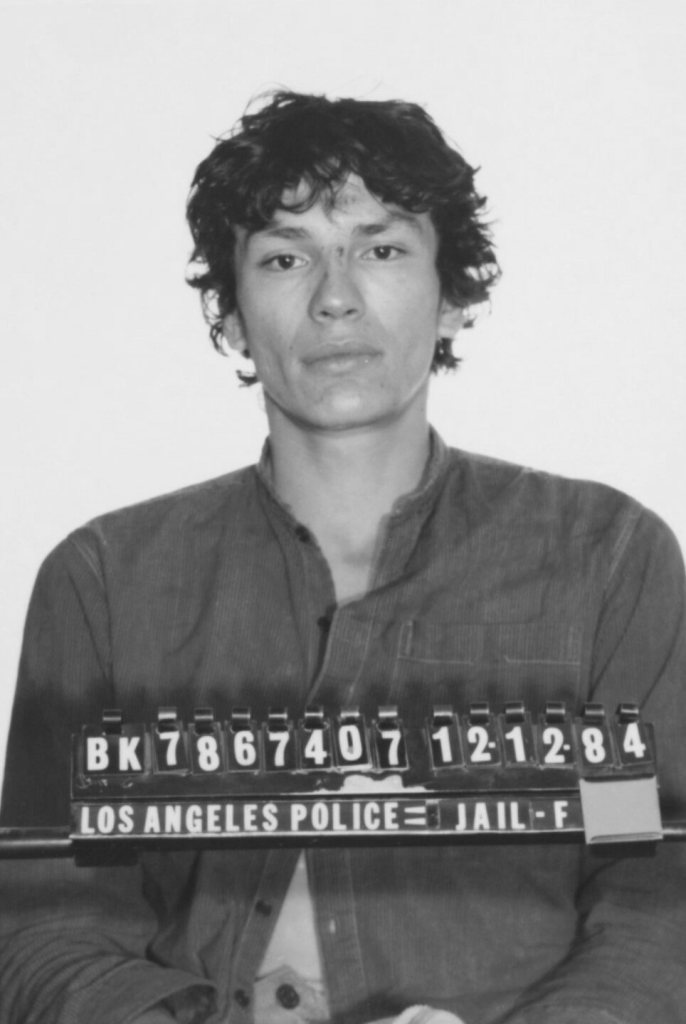

Somkid Khovananth has always been viewed as the most significant Night Stalker eyewitness. She saw him with the light on; it was daylight when the killer departed. She was the survivor who helped police to create the infamous sketch – the one police chose for their BOLO bulletins. The appearance of the suspect in previous murders was later retrofitted by detectives. Those investigators appear on documentaries falsely claiming that all victims described this dishevelled man with stained, gapped teeth.

A subsequent victim, Sakina Abowath, told police about a blonde man (on the first responder report) which later transfigured into light brown hair, then just “brown”, then to Richard Ramirez’s near-black. It suggests a combination of media influence and potential police manipulation.

We’ve never seen Somkid Khovananth’s police statement, only a press release. For some reason it was never included in the appeal exhibits and it has left a critical information gap: how she described the suspect to the first detectives at the scene. Its omission could be seen as suspicious. Was there a reason it has been concealed and not released to the appeals team?

Recently, new details emerged from the March 1986 preliminary hearing transcripts. It transpired that Khovananth also changed her initial description. Then when defence attorney Daniel Hernandez cornered her in court – obviously in possession of her police statement – she suddenly couldn’t understand English and invented new meanings for words.

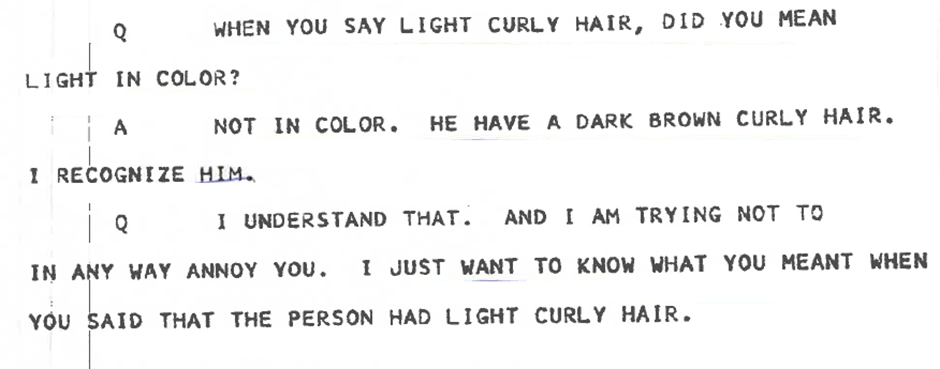

Here is some of the transcript. It was quite maddening to read. Somkid Khovananth had originally reported the suspect as having light brown hair, but she quickly backtracked and corrected herself to “dark brown.”

When asked to confirm that she told LAPD Sergeant Leroy Orozco that the suspect had light brown hair, Khovananth meanders off into the texture of the killer’s curls. She appears to be comparing the tight curls in her composite sketch to Richard Ramirez’s mugshot, with his loose curls. Now she claims that “light” is her word for “loose”.

HERNANDEZ: Did you describe this person as having brown curly hair?

KHOVANANTH: Yes. Light. Not dark brown.

HERNANDEZ: Light brown?

KHOVANANTH: No. Dark brown. Not light brown.

HERNANDEZ: Dark brown?

KHOVANANTH: Yes.

HERNANDEZ: Did you ever talk to Mr. Orozco here on my left about the description of this person?

KHOVANANTH: Yes.

HERNANDEZ: And did you tell him that the person you saw had light curly hair?

KHOVANANTH: Really, yes. It’s not curl- actually, that picture is not very look like really curly hair. He have very light curly hair.

Daniel Hernandez was unconvinced and pressed her to clarify. Instead, Khovananth’s answers became muddled before she abruptly insisted that she could identify Ramirez as the killer. Somehow, Judge Nelson considered that an adequate response.

HERNANDEZ: Can you tell me what you meant by light curly hair?

KHOVANANTH: He’s not really – that picture is really similar. The picture I can identify him.

Hernandez continued to press her, but she held firm, claiming she had always said the suspect’s hair was dark like Ramirez’s. And in case there was any doubt, she repeated that she recognised him – dodging the question entirely. Here, she is clearly becoming hostile.

HERNANDEZ: When you say light curly hair, did you mean light in colour?

KHOVANANTH: Not in colour. He have a dark brown curly hair. I recognize him.

HERNANDEZ: I understand that. And I am trying not to in any way annoy you. I just want to know what you meant when you said that the person had light curly hair.

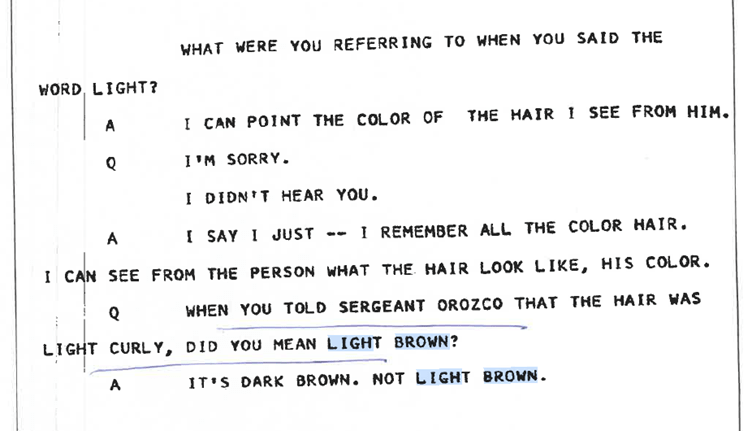

Daniel Hernandez was determined to get it out of her, but again Khovananth deflected, saying she could point to Richard Ramirez’s hair to show what colour it was. She knew she had described the suspect as having light brown hair in her statement, but now she was one step away from looking like a liar.

Her attempt to redefine “light” as “not very tight curls” is linguistically implausible – she clearly did once say “light brown hair,” and now she’s trying to retrofit that to match Ramirez’s darker appearance.

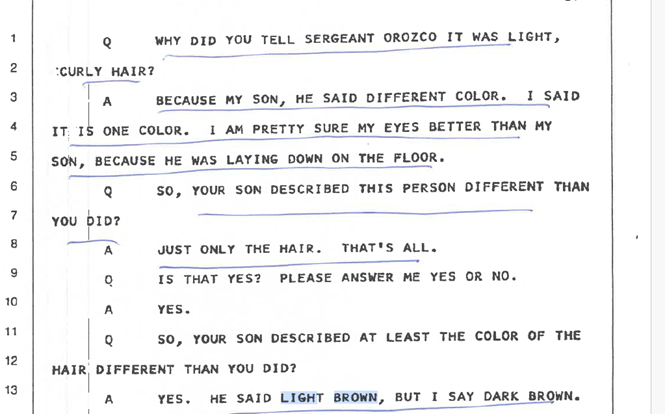

At this stage of the preliminary hearing, Ramirez’s defence team actually performed reasonably well. Daniel Hernandez did what a good defence lawyer should: he pinned Khovananth to her earlier description. Finally, she conceded that she had originally reported a light brown-haired suspect – but now offered a new excuse. It wasn’t her error, she said, but her son’s. Because he had been lying on the floor during the attack, he supposedly saw the colour differently, and she agreed to let the detective write it down that way.

HERNANDEZ: Why did you tell Sergeant Orozco it was light, curly hair?

KHOVANANTH: Because my son, he said different color. I said it is one color. I am pretty sure my eyes better than my son because he was laying down on the floor.

HERNANDEZ: So your son described this person different than you did?

KHOVANANTH: Just only the hair. That’s all … He said light brown. But I say dark brown.

It seems implausible that a mother would allow her eight-year-old son to dictate the final eyewitness description on a police statement – especially when she had spent far more time face-to-face with the attacker. Her later claim about her son’s conflicting memory (“he said light brown, but I say dark brown”) actually reinforces that at least one of them – and most likely both – originally said “light brown.”

In terms of witness reliability, that represents retroactive contamination. The first description given is generally the most trustworthy, as it precedes any external influence such as media exposure or police suggestion. At the time of the Khovananth attack (20 July 1985), there was little public awareness of a “Night Stalker” – the crime was reported simply as a robbery gone wrong. Yet Khovananth later denied that her recollection had been influenced at all.

Los Angeles Times, July 21, 1985. The Newspaper Lie

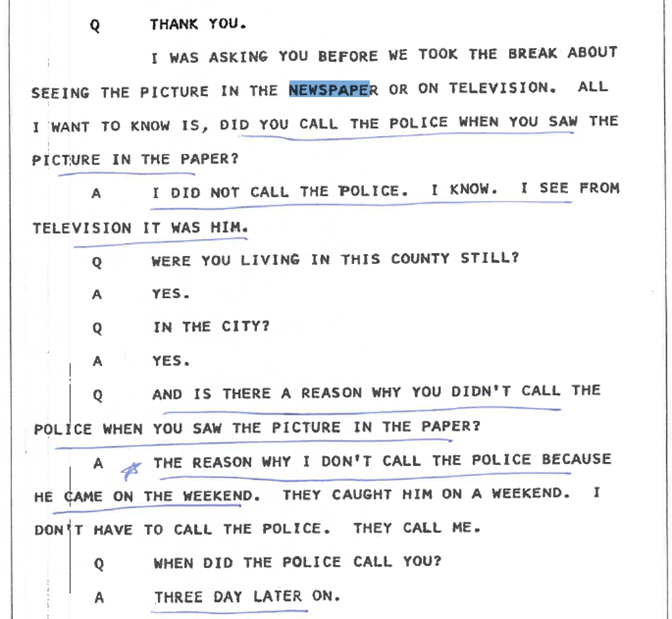

Daniel Hernandez sought to establish how much exposure Khovananth had to the media before identifying Ramirez. By late August 1985, newspaper and television coverage of the Night Stalker was in overdrive. Ramirez’s mugshot aired on TV the night of August 30 and appeared in the papers the following morning.

HERNANDEZ: All I want to know is, did you call the police when you saw the picture in the paper?

KHOVANANTH: I did not call the police. I know. I see from television it was him.

HERNANDEZ: And is there a reason why you didn’t call the police when you saw the picture in the paper?

KHOVANANTH: The reason why I don’t call the police because … they caught him on the weekend.

Khovananth’s reply is simply that she recognised Ramirez on TV but didn’t tell police because it was the weekend. It’s an illogical excuse – mere recognition of her husband’s murderer should have prompted urgency. Her admission that detectives phoned her three days later only reinforces that she made no effort to contact them once the weekend had passed. She then shifts the blame, claiming it was the police’s duty to call her – an excuse echoed by other witnesses who also failed to contact detectives. It suggests they were coached to justify their silence should this question arise.

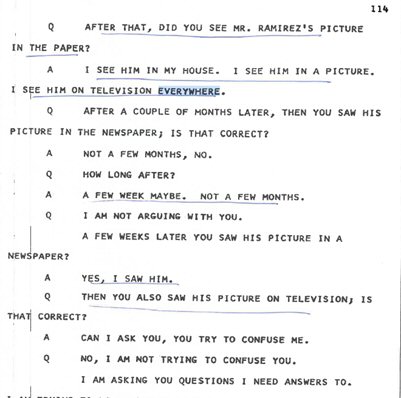

Next, Hernandez asked whether she saw Ramirez’s mugshot in the newspaper before or after his arrest. Khovananth grew confused over whether he meant the composite sketch or the real photograph. She said she remembered seeing both – first the sketch in early August, then Ramirez’s real face after the 30th. But when Hernandez asked her to confirm that she had followed newspaper coverage, she suddenly claimed she couldn’t tell the difference between drawings and photos, asking him to repeat questions as if she no longer understood English.

When Hernandez moved to specific dates, she said it was too long ago to remember. Yet if she cannot recall that, how can her memory of the attacker – from even earlier – be considered reliable?

The contradictions continued. When asked whether she kept up with the Night Stalker story, Khovananth admitted, “I follow the newspaper because I wanted to know if they caught him.” But only a few questions later, she insisted she didn’t read newspapers at all – she only watched television.

KHOVANANTH: I just only see it on television. I don’t read newspaper. At that time I was upset. Who can read anything?

HERNANDEZ: So, you didn’t read the newspaper?

KHOVANANTH: No. I know him. I don’t have to read the newspaper.

Realising she was tripping over her own lies, Khovananth returned to her rehearsed script – that she knew and recognised Ramirez as the killer – before retreating again behind her claim of not understanding English.

HERNANDEZ: When did you become aware that this person that had been in your house was called the Night Stalker?

KHOVANANTH: Can you repeat that question?

HERNANDEZ: When did you become aware yourself that the person in your house was being called the Night Stalker?

KHOVANANTH: I don’t understand your question.Hernandez asked for a translator, but Judge Nelson denied the request. That refusal ensured her contradictions went untested, allowing her to hide behind confusion and waste time with repeated ‘I don’t understand’ answers.

Further Media Exposure

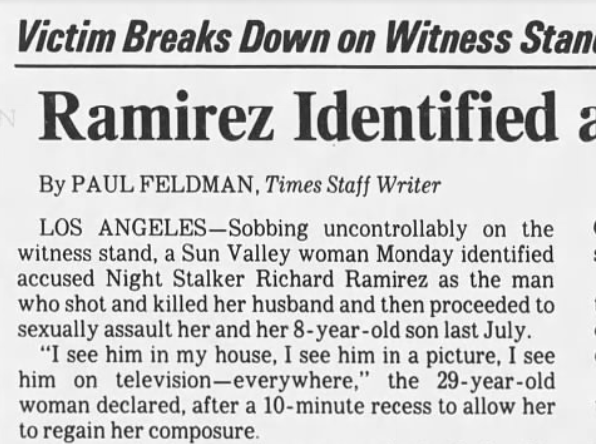

The newspapers reported that she screamed, “I saw him in my house. I saw him in a picture. I saw him on television everywhere!” and described her as sobbing uncontrollably. There had to be recesses so she could collect herself. Yet none of them wrote about her contradictions or lies. Multiple times in this section of the transcript, Khovananth accused Hernandez of trying to confuse her.

Khovananth conflates three separate timeframes and sources – the intruder she saw that night, the composite drawing, and Ramirez’s televised arrest and mugshots. It reads as someone trying to maintain certainty (“I know it’s him”) while avoiding precise timelines that might unravel her identification.

This circular pattern suggests she’s anchoring her memory to media exposure rather than the actual night of the attack. When she says “I see him in my house. I see him in the picture. I see him on television,” she’s blending experiences – a known eyewitness phenomenon called source confusion or memory integration. In short, she’s re-remembering the man through the lens of Ramirez’s media image, which is exactly what Daniel Hernandez was pressing her to admit. When caught, she lied to preserve that illusion of certainty.

Emotional Control

There’s also a degree of emotional control at play. Each time, Khovananth reverted to the lines she rehearsed with Philip Halpin: that she saw Richard Ramirez in her home and that he was the same man in the newspapers and on her television set. These were said in a dramatic and hysterical manner that won the sympathy of the press – who never mentioned the “light brown hair” statement. She also cried about remembering Ramirez’s “big eyeballs and rotten teeth” that played into the media image of the Night Stalker. This does not match others’ descriptions.

She attempts to flip roles and attempts to take control of the exchange: “Can I ask you? You try to confuse me” and “I told you I see this man in my house. He sit right there next to you.” She seizes emotional authority to neutralise or stop cross-examination. That’s often seen when a witness has been rehearsed or feels pressure to “perform” conviction.

Khovananth’s trauma was genuine; the attack was horrific, and trauma alone can distort memory. That much is undeniable. But her recollections are inconsistent, defensive, and at times theatrical. The sudden outbursts toward Ramirez appear scripted by Halpin, designed to sway the press (there is no jury in a hearing).

When cornered, she shifted into a victim-authority role instead of giving a direct, credible response – something as simple as, “Yes, I saw him on TV and in the papers, but I recognised him instantly from his features.” Such an answer would have addressed the contamination issue. Instead, she spun in circles, avoiding any admission of media influence while simultaneously letting on that she had followed the case.

Her confusion, then, seems strategic rather than linguistic. Her English was broken but functional; she had lived in the U.S. for a decade. She had no difficulty under direct examination by Philip Halpin, and she clearly understood Hernandez’s questions and recognised when he was cornering her. When that happened, she used shields: “You try to confuse me” or “I cannot answer your question.” This reads as a defensive mechanism – protecting not her trauma, but the contradictions between her original statement and the prosecutor’s coaching. It’s likely Halpin warned her that the defence would “try to trick her,” priming her to interpret every challenge as manipulation.

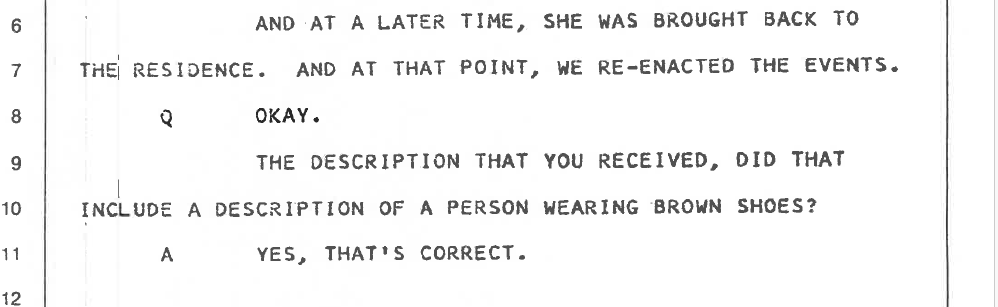

Shoes

One last thing: without going into the Avia shoes saga, it is important to note that the alleged sneakers were an uncommon size 11.5 black Avia Aerobics 445B models. This was based on an unproven theory that the killer was clad in black. However, Khovananth never said he wore black. He had brown pants, a blue shirt with either multicoloured patterns or stripes on. And according to the statement Daniel Hernandez had, brown shoes.

Khovananth described them as “very heavy”, “leather”, “army shoes” and that they were black. She told Daniel that she told police the shoes were black.

However LAPD Detective Brizzolara, who took the statement, later testified that she did indeed say brown shoes.

Here, a pattern emerges with other incidents. Sakina Abowath said that her attacker wore heavy lace-up boots that he removed before the rape. This also matches with Inez Erickson allegedly telling a neighbour that the intruder wore “combat boots.” But Night Stalker Task Force members claimed that Kinney Stadia sneaker prints were found in the Abowath’s house, never boot prints. Perhaps all three witnesses were confused and mistaken. But this looks like an interesting connection. Since we know that the Avias weren’t really rare – and there’s no way of knowing what colour shoes left the prints – we must allow for the possibility that the prints ended up there another way: from a visitor, a prowler or a guest.

-

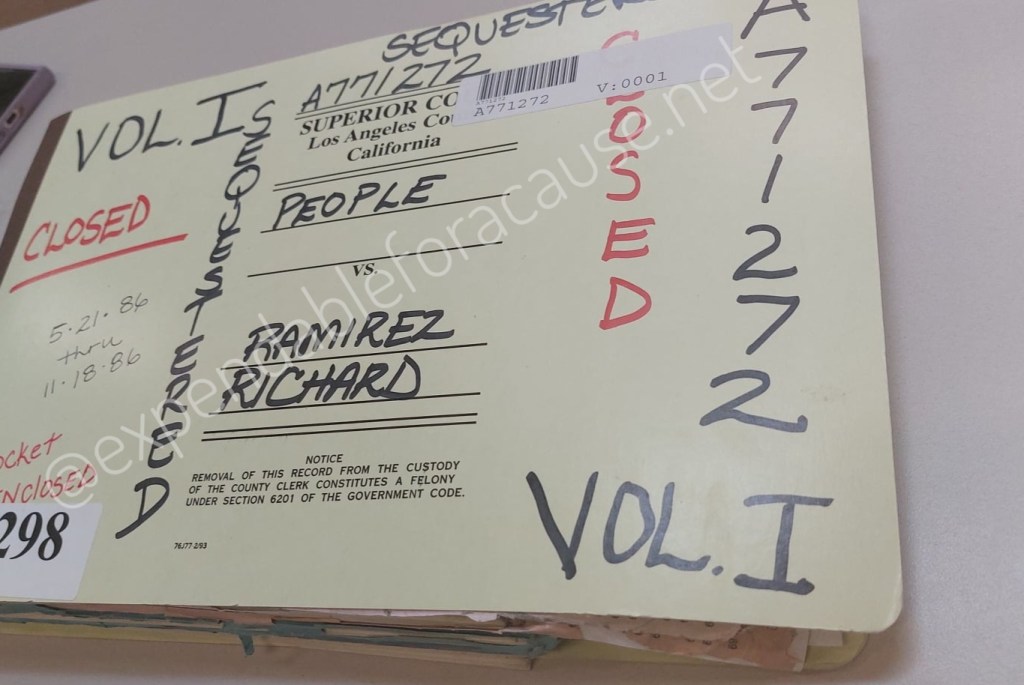

Judicial Bias

You may recall our exciting adventure to the Los Angeles Archives and Records Center last October in the hope of finding some key legal documents. While we were able to obtain several trial documents, we were unable to access all the volumes from the LA trial due to time constraints; however, this did not deter us.

After returning to our respective homes, we were still determined to obtain documents from volumes 4, 5, & 6 – there were 9 in total. Motivated by our commitment to uncovering the truth, we rolled up our sleeves, persevered through months of less-than-enthusiastic writing, and unleashed a flurry of phone calls that would make any telemarketer envious. With every frustrating, “Sorry, that’s not public record” response, we could practically hear the collective eye rolls from our side of the phone. Our persistence finally paid off! At long last, we’ve obtained a small number of trial documents, mostly legal motions referring to things that we could probably recite in our sleep. But hey, every little bit counts, right? Is it everything we hoped for? No, but it adds another layer to understanding this already complex case.

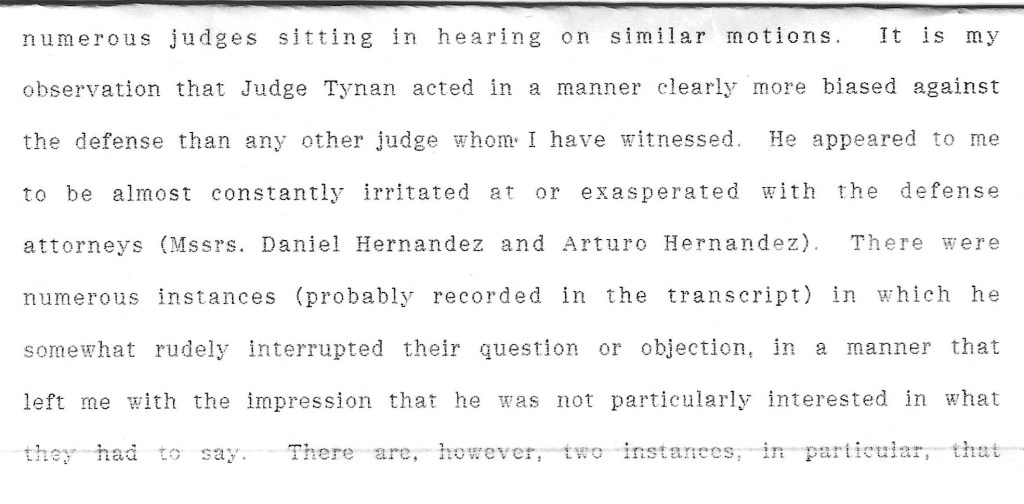

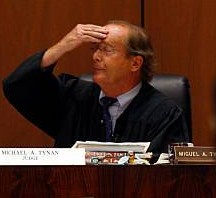

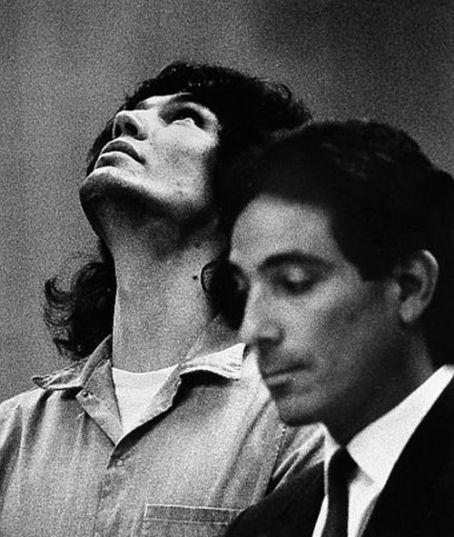

Amongst the various motions we recently received from the Los Angeles Archives and Record Center, we found a declaration from an expert witness that provides insight into Judge Tynan’s courtroom behavior and his stance toward the defense during the trial. This declaration strongly suggests that Judge Tynan displayed a troublesome bias against both the Hernándezes and Richard. We have previously noted instances of bias in Judge Tynan’s rulings and objections, which clearly favored the prosecution at the expense of the defense.

However, this is the first time we’ve encountered explicit mention by anyone directly involved in the trial, aside from the defense attorneys, of the bias that influenced the courtroom dynamics.In 1987, the Hernándezes arranged for John Weeks, a demographic and statistical expert witness, to examine the jury selection process in the Ramirez case, explicitly addressing the small number of Hispanics drawn from the population as potential jurors. John Weeks was a distinguished Professor Emeritus of Sociology and the Director of the International Population Center at San Diego State University. He had decades of experience in research, writing, publishing papers, and consulting. He had also served as an expert witness in numerous legal cases, representing both the defense and prosecution.

Weeks submitted a declaration to the court, although it is unclear to whom it was specifically addressed; the document is marked as having been received on July 1, 1988. Having served as an expert witness in multiple criminal cases in Los Angeles, San Diego, and Riverside counties, Weeks had observed numerous judges presiding over legal motions. In his declaration, he stated that Judge Tynan demonstrated a level of bias against the defense that he had never encountered with any other judge. Weeks noted that Tynan often appeared “irritated and exasperated” with the Hernándezes during the proceedings. He also observed Tynan rudely interrupting the defense’s questions and objections on numerous occasions, suggesting a lack of interest in what the defense attorneys had to say.

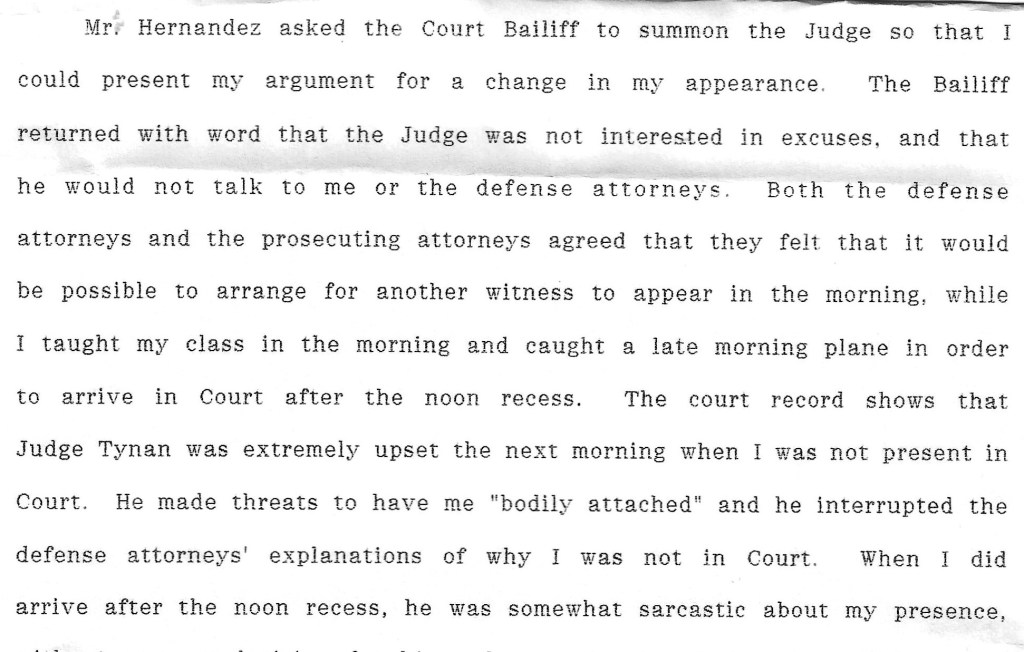

Declaration of Dr John Weeks, 1988 John Weeks vividly recalls how his testimony was abruptly cut short by an end-of-day recess on one occasion. Judge Tynan ordered him to return to court the following morning, showing no concern about whether this would conflict with Weeks’ professional commitments. Faced with this dilemma, Weeks informed Daniel Hernandez of his inability to attend court the next morning. In response, Hernandez called upon the Court Bailiff to summon Tynan for a discussion. However, the bailiff returned without Tynan and conveyed that the judge had no interest in listening to excuses and refused to engage with either Hernandez or Weeks. When Weeks did not appear in court the next morning due to his teaching obligations in San Diego, Tynan became furious, threatening to have him “bodily attached”, meaning that Tynan would issue a warrant for Weeks’ arrest and have law enforcement bring him to court. He dismissively ignored the defense’s explanation for Weeks’ absence, showing a complete disregard for the circumstances. Weeks reported that he arrived later, during the noon recess, at which point Tynan displayed a sarcastic attitude toward him. Tynan neither apologized for his rudeness the previous day nor acknowledged Weeks’ legitimate reasons for missing court. Weeks asserted that Tynan seemed uninterested in the jury challenge motion to which he was testifying and acted in a way that suggested he simply wanted to dispose of the motion as quickly as possible.

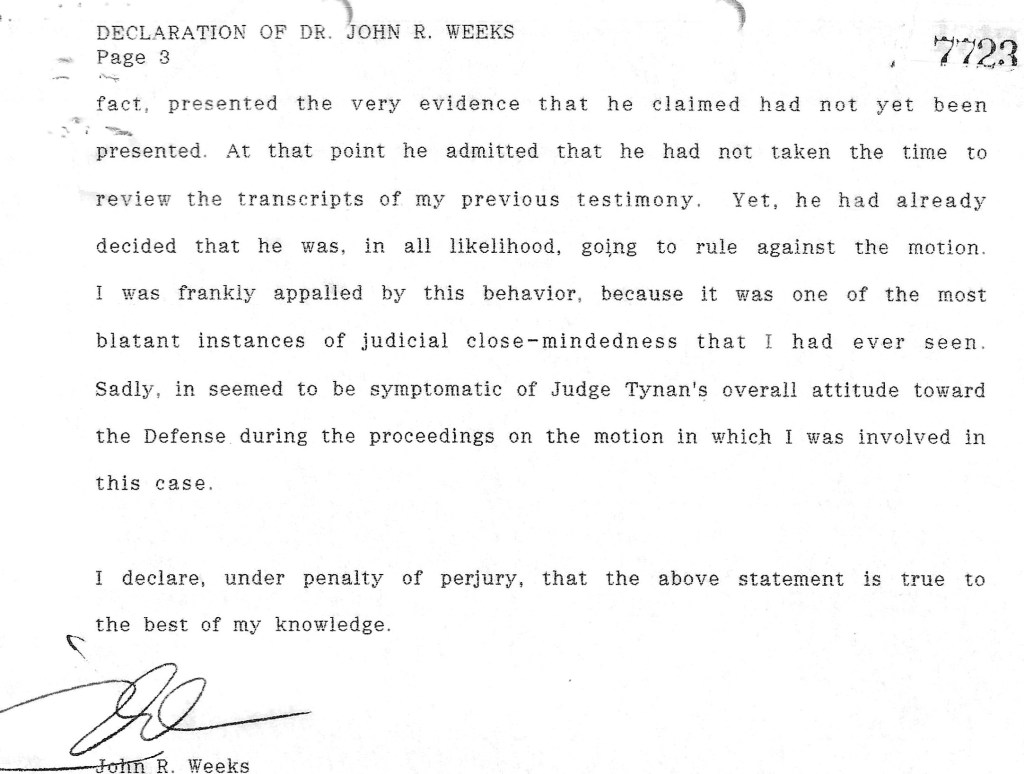

Declaration of Dr John Weeks, 1988 Weeks appeared in court again at a later date to continue his testimony regarding jury selection. He reported that as he was finishing his direct examination, Judge Tynan stated that he had not been presented with the basic facts that Weeks was discussing, specifically the disparity in the number of Hispanics selected as potential jurors. Because of this, Tynan was inclined to deny the motion. The defense pointed out to Tynan that Weeks had indeed presented the very evidence he claimed to have not seen. At this point, Judge Tynan acknowledged that he had not taken the time to review Weeks’ prior testimony; however, he had already decided that he was likely to rule against the motion concerning the matter of Hispanics on the jury panel.

Weeks expressed his dismay at Tynan’s behavior, describing it as one of the“most blatant instances of judicial close-mindedness” he had ever witnessed in his many years as an expert witness. He further stated that this behavior reflected Judge Tynan’s overall attitude toward the defense during the time he was involved in the case.

Declaration of Dr John Weeks, 1988 From the available information, it’s clear that Judge Tynan made absurd rulings, ignored precedents and court rules, overlooked legal errors by the prosecution, and appeared to exhibit inherent biases towards the defense. It appears that Judge Tynan wasn’t interested in fairness or justice. But then what else should we expect from an LA Superior Court judge working for one of the most corrupt judicial systems in the nation?

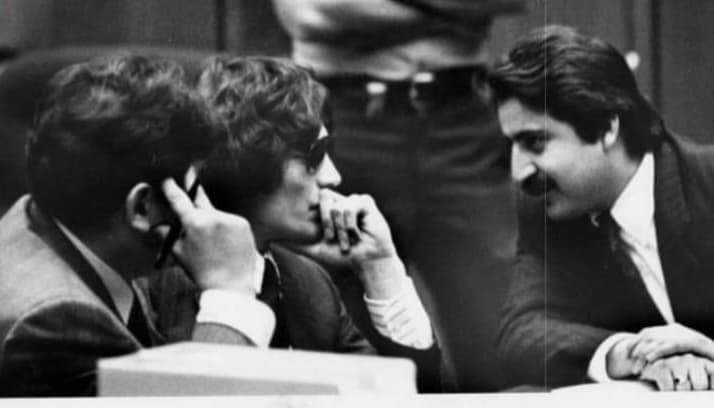

Judge Tynan looking exasperated (perhaps after a day of listening to the Hernandezes and Halpin going at it). And onward we continue…

Why do we continue the quest for trial documents and other materials? Because of a genuine interest in untangling the convoluted web that permeates every aspect of the Nightstalker case.

Our mission? To uncover the truth that has been buried in the California legal system for decades, out of public awareness, and to sift through the legal maze and uncover the documents that hold the key to exposing the intricate, sensationalized story. We aim to continue to find and divulge the essential documents that can shed light on the railroading of Richard Ramirez.

The journey is far from over.

We look forward to sharing our findings with you. Stay tuned for updates as we continue in our efforts to unravel this story piece by piece

KayCee

-

Forty Years

On August 31st, 1985, the hunt for the Night Stalker ended, and the circus began.

The following is an excerpt from our book “The Appeal of the Night Stalker”. See the link at the end of this post for details.The Capture

Richard Ramirez, travelling to Arizona and back, missed the release of his mugshot on the evening news. Unbeknownst to him, police and the Special Investigation Section officers were staking out the Greyhound bus depot and were willing to kill him on sight. As if California were the Wild West (which some might argue that it still is), Ramirez was wanted dead or alive, but preferably dead; the SIS team is unofficially known as the ‘Death Squad’. Carrillo admitted that part of him wanted Ramirez to be killed.

The Greyhound Bus terminal, from a 1970s image. Ramirez, coming through the inbound entrance instead of ‘escaping’ through departures as expected – left the station and headed to a liquor store to buy snacks. There he saw his own face – not a lame composite- on the front of a newspaper naming him as the prime suspect, and he ran. He jumped onto another local bus, but again his appearance drew attention from the passengers. He felt he had no choice but to leave the bus and continue on foot, probably heading for his eldest brother Julian’s house.

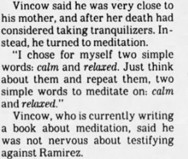

Frightened and not thinking rationally, Ramirez ran across a freeway, jumped a tall soundproofing wall, vaulted over fences and traversed down alleys into the Hispanic-populated barrios of Boyle Heights, East Los Angeles. While the Night Stalker had hitherto been a nebulous shapeshifter, once the nation was shown Richard Ramirez’s face, he was instantly recognisable in a way he never was to his alleged victims.

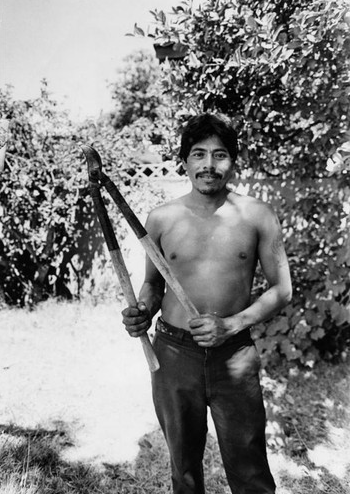

Multiple people saw him. A man watched him jump off the Santa Ana Freeway’s barrier wall and land on the hood of a car, before running down an alley. On East 7th Street. A resident saw Ramirez “lurking” and telling his Doberman to be quiet because he was “tired”. Ramirez then jumped the fence. He was seen emerging from an alley on Siskiyou Street looking nervously all around him. On South Indiana Street, he attempted to carjack a woman but was chased away, climbed up a six-foot high wall and dropped into nearby Percy Street, where again, he was recognised immediately by a woman in her garden. He was pursued by her son, who was brandishing pruning shears. At another house, Ramirez knocked on a door and, holding his throat, begged a woman for a drink of water. Recognising him, the resident reacted by screaming and calling the police.

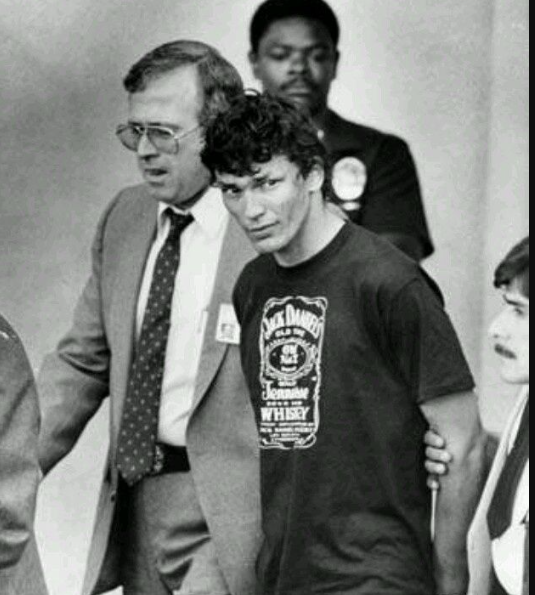

Rosalio Dimas pictured here with his garden shears. The image ran in the newspaper on September 1st, 1985 and September 21st, 1989. Credit: Leo Jarzcomb, Herald Examiner Collection. By now, police helicopters were circling above. Finally, turning onto East Hubbard Street, Ramirez attempted to steal a car and, when this failed, he attempted to carjack another woman. This ignited rage in neighbours who gave chase, with one vigilante ‘hero’ striking Ramirez over the head with a metal bar. Amid the commotion, the residents did not realise they were beating up the most wanted man in the USA, until somebody shouted, “Es el matón!” (it is the killer). The police were called, and another 25-year-old Ramirez arrived on the scene in the form of Deputy Sheriff Andres Ramirez. He was informed by resident Manuel De La Torre that Ramirez had attempted to steal his car and assault his wife.

It was not until the deputy asked for his name (Ramirez told him his given name, Ricardo Ramirez) that the ‘penny dropped’. Deputy Ramirez began to worry as residents converged on the patrol car, yelling in Spanish that they should “get him”.

Ramirez was placed under arrest for attempted carjacking, grand theft auto and assault. He was unarmed, compliant and non-aggressive. The most evil man to walk the streets of Los Angeles was apparently not carrying a weapon, although it was later claimed he drew a knife when attempting to carjack and that he threw his gun away. This resulted in police searching the streets and suggesting one of the Hubbard Street residents had taken it for themselves. No gun was seen or recovered, much like the other weapons Ramirez was accused of using. If Ramirez had a gun or knife that morning – and was the Night Stalker – surely he would not have hesitated to use them when running for his life.

In fact, when interviewed on tape by Philip Carlo, Ramirez said:

“I turned at all the people around me and I spit at them (sic) I poked my tongue out at them. I stuck it in and out, you know, like a serpent… If I would’ve had a pistol, I would’ve made them scatter. They wouldn’t be as brave as they thought they were.”

It is conspicuous that he said if he had a gun, he would have merely pointed it at them instead of firing. Instead, the ‘terrifying, Satanic Night Stalker’ poked his tongue out at them like a child.

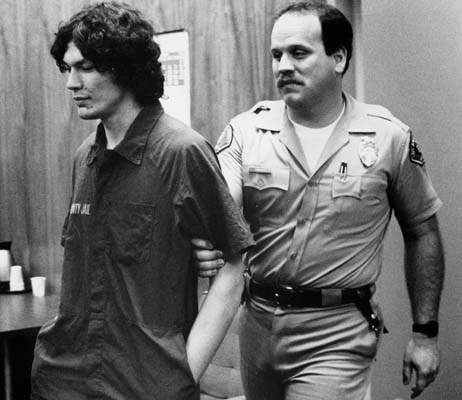

Los Angeles Mayor, Tom Bradley, declared no trial was necessary and handed out awards. He had an election to win. Credit: Chris Gulker, Los Angeles Herald Examiner Collection. Ramirez was exhausted and dazed, and bleeding heavily from being assaulted, so an ambulance was called. He was alleged to have said in Spanish, “thank God you came,” when the police arrived. After his capture, Mayor Tom Bradley stated that there was no need for an “arbitrary legal process” because he was already “satisfied” that they had “found the right man” before the veracity of the evidence was tested. It was clear that a trial was not an ideal outcome. Alas for law enforcement, Ramirez was handed over very much alive, his head wounds treated and completely covered in gauze bandages. That is, until they were removed so that Carrillo, Salerno and others could be seen escorting Richard back to Hollenbeck Station with blood visible down the back of his neck and over the collar of his shirt.

Sgt Frank Salerno and his famous ‘perp walk’. (Carrillo, marching ahead, was cropped out of the shot). Credit: Mike Sergieff, Los Angeles Herald Examiner Collection. On 3rd September, two award ceremonies honoured the citizens instrumental in taking the infamous Night Stalker off the streets – all before he had been identified, arraigned or even charged. Deputy Ramirez also received an award, yet he was merely doing his job – responding to a carjacking.

The “Hubbard Street Heroes”, including Deputy Andres Ramirez, receive their awards. Credit: Mike Sergieff, Los Angeles Examiner Collection. And the wheels of ‘justice’ began to turn.

Fast Forward

Over the years, the narratives surrounding this case have evolved and intensified. Carrillo, who was not originally the lead detective and was seldom referenced in contemporary newspapers, has since emerged as the prominent figure of the Night Stalker Task Force, surpassing even Salerno in public recognition.

Current media, including documentaries and podcasts, frequently revisit this case, yet still fail to address essential questions. Four decades on, many uncertainties persist. Our approach was to look beyond sensationalism and superficial treatments, committing ourselves to in-depth analysis. The investigation began with a review of approximately 1,000 pages of court documents and culminated with direct access to the original case files in a basement in Los Angeles. Research is ongoing, and we believe that the full truth of this case remains elusive.

There have been accusations that our work asserts Richard’s innocence; however, a thorough reading will demonstrate that such claims are not made. Instead, we maintain that the case did not undergo rigorous testing and that proceedings were notably biased toward the prosecution. We present evidence indicating that the judicial process was perfunctory, a box-ticking exercise, making any alternative verdict highly improbable in the context of the Night Stalker case.

Venning consolidated our collective findings into a comprehensive volume that avoids sensationalism, refrains from fabricating victim dialogue, and does not speculate about the perpetrator’s thoughts or invent scenarios that did not happen. Our work provides readers with the resources necessary for a critical examination of the case, free from hysteria, leaving any interpretation firmly in their hands.

Coming Up…

Although there has been a period without updates, the team has remained actively engaged. As previously stated, we are committed to sharing any significant developments as they arise. Recently, following extensive communications with the relevant authorities, we have obtained additional information. This process is gradual, as documents are being received incrementally and require thorough review. At present, most of these materials consist of motions filed during the pre-trial phase – and never seen in public before – which correspond with our ongoing investigations. We have also requested further documentation and will continue to compile and share pertinent findings as they become available. There may be some disruption to a few posts as we update, or split into two, etc, so please bear with us.

The first volume we were allowed to examine in LA. During this time, feel free to ask us any questions, and we’ll do our best to answer. We welcome serious, intelligent input.

We would also like to extend our sincere thanks to those who have read our book and shared valuable feedback; your support is greatly appreciated.Source: The Appeal of the Night Stalker: The Railroading of Richard Ramirez (click the link to buy your copy)

-

We Are Not Saying ALL the Police Were Involved in a Grand Conspiracy

Some people accuse us of claiming that all the police – from multiple agencies – were all involved in a grand plot to “put an innocent man in jail” and they had no motive to mass participate.

That is not what we’re saying.

That isn’t how it would work, anyway.

Here’s what I think happened. Gil Carrillo put forward his hypothesis about the “man in black” who is a “sexual deviant” aroused by seeing fear in his victims’ eyes. Carrillo’s hypothesis meant that the killer had no M.O. and their fate rested on whether they fought or “acquiesced” to the Night Stalker’s demands.

None of the other detectives believed him, not even his partner Sergeant Frank Salerno. Their lieutenant, Tony Toomey, was uninterested. At the Bennett incident, this changed. There, Salerno saw the shoeprint and then asked Carrillo to tell him all his theories. This was explained by both men on the Netflix documentary.

Now, Carrillo had convinced someone who would be taken seriously – Salerno already had an important role in the Hillside Strangler case. According to the biographer Philip Carlo, Salerno was made acting lieutenant for team 3. This cannot yet be verified this anywhere else, and Carlo is often inaccurate. But there it is.

This next section says Captain Bob Grimm put Salerno in charge of forming a task force.

If this is correct, then Gil Carrillo had the ear of the man now leading the task force – Salerno – and everyone else was following Salerno’s orders. They had no authority to question them and would have assumed the information Salerno was giving them (via Carrillo) was correct.

MONTEREY PARK PD

I also wrote in the book about how Carrillo involved himself in Monterey Park crimes. Monterey Park has its own police department. Some cases were eventually given to the Sheriff’s Department – the Yu case (originally thought to involve a Chinese spy, and the Dickman case. Carrillo also showed up at the Doi crime scene and due to the presence of shoeprints, the Sheriff’s Department was also involved in the Nelson murder.

In the early July newspapers, the killer was announced to be a tall, thin, curly-haired man. We know from their statements that this is untrue. My book showed that this character was based on Richard’s alias “Richard Mena.” But once the Sheriff’s department controlled the Monterey Park cases and it was circulated in the media, all the Los Angeles County police departments were on the lookout for this false suspect.

LAPD & GLENDALE PD

After the Khovananth and Kneiding attacks on 20th July 1985, the Khovananth composite drawing was released. The Khovananth incident was dealt with by the Los Angeles Police Department, so now they were involved and created their own task force. The Kneiding incident came under Glendale Police Department, so they also became involved. Can you see how it’s snowballing?

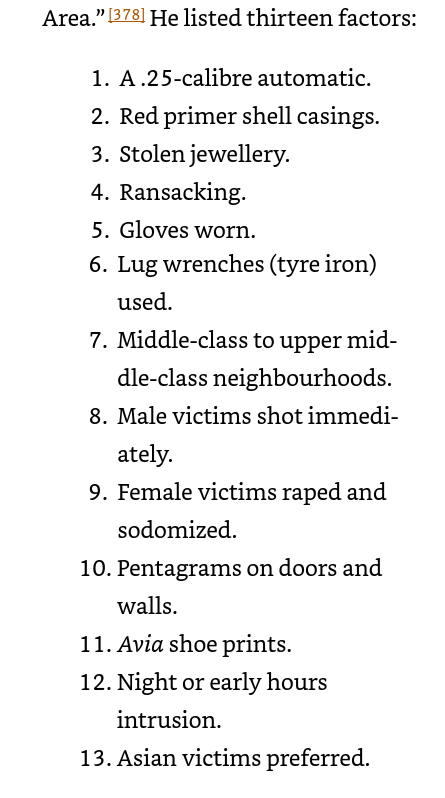

During this period, Sergeant Christansen was in charge of firearms examination. He originally declared that the Kneidings and Chainarong Khovananth were shot with a .25 calibre ACP. Note: This was not the final evidence submitted by the prosecution at trial.

SFPD

It was an officer from Glendale Police Department that heard about the Pan murder in San Francisco. He heard there was .25 ACP shell casings at their crime scene and contacted them. He thought the 20th July cases were related to Pan.

The mayor of San Francisco then “revealed” that the .22 bullets had been used in a “dozen” Los Angeles cases. Both Kneiding and Khovananth were later declared to be separate .22LR revolvers. But you can again see how this is escalating. It was all being televised.

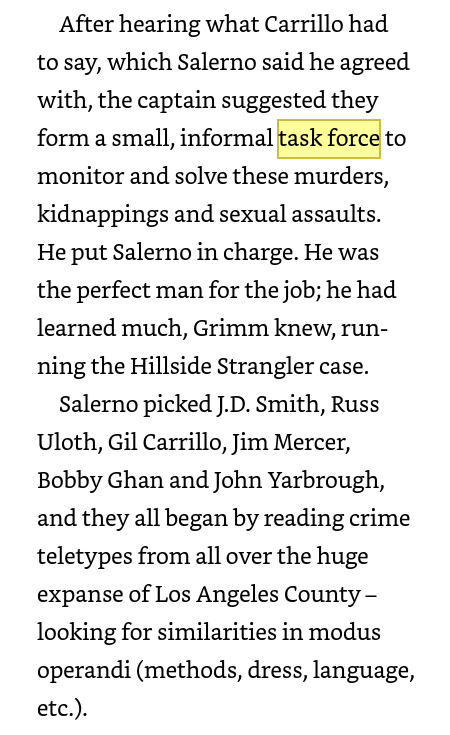

San Francisco were given a list of what features to look out for now that the Night Stalker was up there. This list was shared from the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department. This means the LASD was influencing how the SFPD examined their own cases.

From my book! Please buy it! Carrillo and Salerno were assisting them and flew up there to examine the crime scene – and were followed by news reporters. There was no chance of separating the San Francisco murder from the ones down in Los Angeles. There was now no independence from the Night Stalker machine.

THE OCSD

Then the Night Stalker allegedly hit down in Orange County, which has its own Sheriff’s Department. But Carrillo and Salerno headed down there too – also with the media.

Then all the informants crawled out and Carrillo and Salerno were not heavily involved in all that aspect of the investigation – it was led by Sergeant John Yarbrough. The rest of the task force and team took over dealing with stolen property, interrogating Ramirez’s associates and allegedly physically intimidating the fence, Felipe Solano. Meanwhile, up in San Francisco, Inspector Frank Falzon punched Armando Rodriguez so he would co-operate.

There was no rowing back from this – the police become tunnel-visioned. The media hysteria put them in a race against time. Politicians were becoming involved and putting pressure on the LASD and LAPD. The phones were ringing off the hook with sightings. There was no time for random detectives to say to Salerno, “Oh, hold on, let me just read all the victims’ original statements. I just need to check that we’re pursuing the right guy.”

The Assistant District Attorney was then desperate to take the case – they all want to prosecute the big names – he’s not going to question the evidence because it will humiliate multiple police forces. Someone like Richard Ramirez wasn’t important enough to do that. So they made the evidence fit. Only a few senior detectives were involved, the rest were following orders and one can argue that they too were caught up in hysteria and confirmation bias.

If you want to read about the entire case in chronological order, as well as the trial, please buy the book! Also, thanks to everyone who has taken the time to give us nice reviews. I really appreciate them, they mean a lot.

You must be logged in to post a comment.